Reading this book was just a series of ‘wow’ moments from start to finish, completely unexpected in a non-fiction book and a history of a publishing house at that.

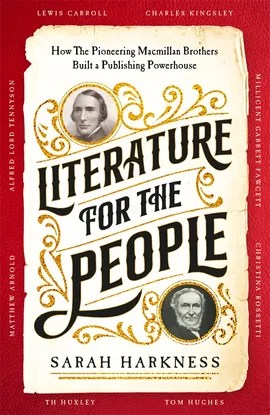

Literature for the People: How the Pioneering Macmillan Brothers Built a Publishing Powerhouse by Sarah Harkness is about the strange early life of the publishing behemouth. Daniel (born 1813) and and Alexander Macmillan (born 1818) were the youngest sons of a crofter and his wife from the Isle of Arran. The Macmillans’ lives were hard and the father Duncan died fairly young whilst his youngest sons were still children. The weight of caring for the family fell on the shoulders of the oldest brothers Malcolm and William Macmillan, who at the time were carpenters.

The five years between the youngest boys made quite a difference to their lives. Daniel had it by far the harder being sent away aged just 10 to be apprenticed to a bookbinder in Irvine for seven years. By the time Alexander hit a similar age Malcolm had sustained injuries whilst working on a building, injuries so severe that manual work now out of the question.

“This must have seemed a disaster to the family, but in fact it forced a change of career, into schoolmastering, which was to have a significant impact on the lives of both his younger brothers Daniel and Alexander. Somewhere along the way, Malcolm had gained sufficient grasp of the elements of a good education, including Latin, Greek, Hebrew and English, to find work as a teacher and rise to head of house. His brother William also became a school teacher and slowly the family began to climb up the ladder out of penury, and to mix with the professional classes of Irvine.” [p.19]

The above is remarkable. For most families the senior male becoming physically incapcitated in the early nineteeenth century would have been truly a catastrophe. Perhaps driven by their deep need to read the Bible, education must have been terribly important to this rural, working class family. For Malcolm to be able to teach himself a range of languages he must have read well in English to read the primers. Bear in mind their father was a Gaelic speaker. They must have prioritised spending to enable schooling and the buying of books and the joining of libraries. This is the first of the very many remarkable facts about the Macmillan family.

Irvine and then Glasgow became too small for Daniel: once he had finished his apprenticeship he, and eventually Alexander, who had much more formal schooling because of the family’s rise in circumstances, moved permanently to England.

The book follows Daniel initally, though his various employments and small business start-ups. Between London and then Cambridge Daniel, followed again by Alexander, learned first and foremost about readers, and about which books sell and why. They ran their shops talking and more importantly listening to their customers. The business gradually became as much publisher as bookshop and we start to see the emergence of the firm of Macmillan that we recognise.

As the firm grew the rosta of writers that formed part of their social group and their publishing business included Charles Kingsley, Thomas Huxley, Thomas Hughes, Christina Rossetti, Matthew Arnold, Lewis Carroll, Tennyson and many more. The early publishing history of these major literary figures and the to and fro between publisher and writer is fascinating. Alexander, combining the roles of publisher, editor, critic and friend had to handle conflicting views of religion, slavery and other controversial subjects, and dealt with arguments between the writers. He remained throught his life a very hands-on boss, dealing personally with many of the issues that came up and managing the many egos and personal tensions involved with great skill. We also see the firm trying to break into the very difficult American market and to move into publishing journals and periodicals.

This makes it sounds like success came quickly, but it did not of course. The men become very successful but worked incredibly hard and Daniel in particular suffered with his health. Both men had the typical large Victorian families and this is as much their story as the story of the Macmillan publishing house. The family achieved immense success intellectually, socially and financially (including, of course, a grandson becoming Prime Minister) but there is also unimaginable tragedy, even by the standards of the day.

Whilst the tale of Macmillan & Co. is definitely the story of the business acumen and literary nous of the two brothers, their wives and a female friend were treated with huge respect by the brothers and featured more prominently than you might think. On the direction of the business and on literary matters the women’s opinions were sought, discussed and acted upon. Of A Book of Golden Deeds by Charlotte Yonge Alexander says, “The title of the little book I spoke to your brother about was suggested by my sister-in-law (who is also my [business] partner) Mrs Daniel Macmillan” [p.181].

The novelist Dinah Mulock (best known for John Halifax, Gentleman) was Macmillan’s first paid manuscript reader: “She was an assiduous correspondent, often working directly as an editor with authors to improve their style or plotting. She was also partly responsible for Macmillan’s 1860 move into books for younger children” [p. 179]. Macmillan became so dependent on her help that she threw Alexander into a panic by the prospect of her unexpected marriage to a one-legged Scottish accountant, George Craik:

“Dinah told Alexander that she intended to marry and move to Scotland with George, and it spurred him into making an unusually rapid decision, concerned by the potential loss of a woman whom he had come to depend upon for literary counsel and contributions. He made enquiries … into George’s business abilities, and two months later offered to make him a junior partner in Macmillan & Co. if the couple would stay in London. It says a great deal for Macmillan’s respect and affection for Mulock, as George was so little known to Macmillan, and had no experience in the publishing trade.” [p.201]

Treating people as people, and not as stepping stones to greater things, seems to have been one of theMacmillan brothers’ many talents. The strong religious belief that they shared always tempered their ambitions. They were always successful but never ruthless. The novelist Thomas Hughes wrote in the preface to his biography of Daniel Macmillan (quoted with much approval by Harkness):

“Whosoever glances at these pages cannot fail, I think, to admit that there was something in this man’s personal qualities and character, apart from his great business ability, which takes him out of the ordinary category – a touch, in fact, of the rare quality we call heroism. No man who ever sold books for a livelihood was more conscious of a vocation; more impressed with the dignity of his craft, and of its value to humanity; more anxious that it should suffer no shame or diminuation through him.” [p.387]

There are many reasons to read Literature for the People: the tale of the two working class brothers and their success is compelling; the insight into Victorian publishing and the ways of the world of letters in the nineteenth century is fascinating; but it is the human story at the heart of it, the family triumphs and tragedies, that have stayed with me. The scholarly reasearch is extremely diligent but Sarah Harkness’ greatest success is in making you totally invested in the outcome of each chapter of the brothers’ lives, in making you root for Daniel and Alexander and their descendants on every single page of the book, so much so that when I got to the end I wanted to read it all again (how rare in non-fiction!). I loved it.

Sarah Harkness has a Substack here.

Leave a comment